For French novellists of a certain generation, the First World War was nothing short of the destruction of civilisation, but they all dealt with it differently. Roger Martin du Gard’s classic, Les Thibault, literally shatters into pieces on the outbreak of the war with the death of the younger of the two brothers at the heart of the novel cycle. Jacques, a revolutionary pacifist, dies an agonising and anonymous death from his injuries in a plane crash in the opening days of the war. The older brother, Antoine, a doctor, succumbs to a gas attack towards the end of the war but main action ends with the death of Jacques – Antoine’s death is a mere epilogue and the novel cycle peters out in a series of increasingly despondent diary entries.

Georges Duhamel omitted the war altogether from his 10 volume family saga, La Chronique des Pasquier. Duhamel wrote extensively about his own experiences in the war as a doctor but maybe it was all too raw to be transcribed into fiction.

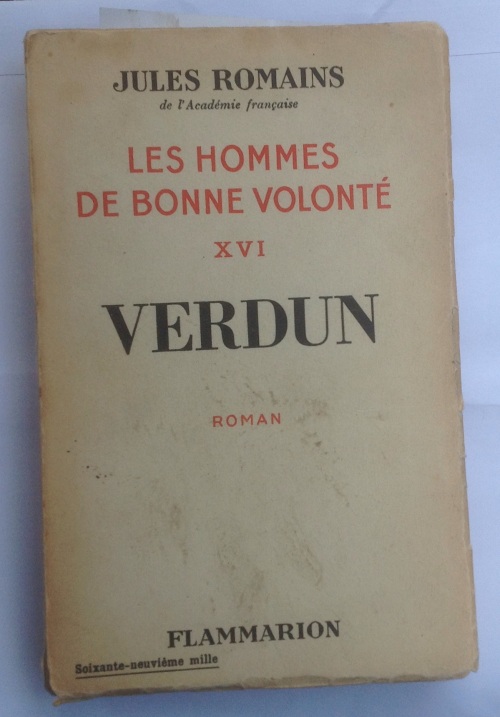

Amongst the writers of the great French novel cycles, only Jules Romains tackled the Great War head on, in the 15th and 16th volumes of the 27 that made up Les Hommes de Bonne Volonté, a grand generational sweep, with a vast cast of characters, through which the lives of two friends, writer Pierre Jallez and politician Jean Jerphanion, act as constant threads of reference. This modern tapestry covered a quarter of a century from 6th October 1908 to 7th October 1933.

The two war volumes focus on the titanic and brutal battle for the French city Verdun, which lasted nearly 10 months between February and December 1916, with nearly a million casualties and 300,000 dead.

Volume 15, Prélude à Verdun, through a series of short TV-like scenes, shows a war that has got bogged down in its second winter, disillusionment at the front and the politicking and scheming in the officer ranks and the French High Command, ensuring that the initial response to the colossal German assault on Verdun was sluggish and ineffectual. The volume ends with the ominous opening salvos of the German attack.

Romains places his fictitious characters amongst but at a slight distance to historical ones, so we meet, for instance, the fatuous, self-serving and self-satisfied General Duroure, not quite in the inner circle of the real French generals, Joffre, Langle de Cary, Herr and Pétain.

For Duroure the war has provided an unexpected boost to his moribund career and he is enjoying his war (with its daily horse rides), apart from the niggling worry that he’s not being taken seriously enough. Things nearly go seriously awry when a plan of Duroure’s to put the wind up a couple of visiting parliamentarians from the Army Commission by eliciting a retaliatory shelling from the Germans comes a little too close for comfort. Duroure is offered the command of Verdun, but declines – so Pétain steps in to save the day.

Jerphanion is a relatively low-ranking officer on the front, closer to his men than to the officer class, realising that this is no longer the short, sharp war that was promised. The Prélude sees his regiment largely away from the action, but by the opening of Volume 16, they are on their way to Verdun.

Another of Romains’ central characters, Clanricard, is a mild, earnest and principled Parisian teacher, is stationed elsewhere on the front. We see him managing by subterfuge to avoid carrying out an order to attack from headquarters that would have resulted in the futile massacre of his men.

All of this relatively low level activity changes with the final words of the novel (apologies for the rough and ready translations):

“On the 21st, at about 7:15am, the cold was sharp and the daylight already clear. The people of Vauquois heard a noise as if the horizon to the East was being ripped apart, as if someone had plunged a knife into the canvas of a tent filled to bursting with water; and a massive rumbling sound started to flow towards them, remorseless, growing louder by the second.”

This was the German bombardment, raining down on the French positions at Verdun as they hurled artillery at them to break this symbolic but difficult to defend crook frontline.

The second novel of the war pair, Verdun, takes some of Romains’ characters into the hell-hole itself.

Every writer looks at war differently and the sheer industrial scale of the horror in the Great War triggered an outpouring of work, much of which remains widely read today. Romains and a number of his contemporaries haven’t fared so well. This relative obscurity is unmerited, in my view. The War is where Romains’ unique perspective, “unanisme”, really comes into its own.

Romains was a clearly out of step with literary fashions in the early decades of the 20th century. The prevailing trend in novel writing in France had already rejected the social realism championed by Zola, for political as well as literary reasons. Arguably Zola’s approach which treated people as components of Society with predetermined fates dehumanised them and diminished the role of the individual (although if you read Zola you will know that his characters often leap off the page). The individual was back at the centre of things by the end of the 19th century and in French literature this would continue all the way through Dadaism, surrealism and existentialism.

Romains went in the opposite direction. He was interested in how groups of people looked as though they behaved as a single entity (hence “unanisme”). A precursor to the hive mind, perhaps. Romains would have been fascinated by Twitter.

It’s not hard to see how moving armies of men can illustrate this idea. Verdun contains some vivid depictions of the fighting itself. But the novel is just as compelling for its descriptions of the chaos inherent in the supposed mechanics of warfare.

In one scene, Jerphanion’s regiment is trying to march to Verdun along the only main road, jammed with vehicles and civilian refugees fleeing in the opposite direction:

“looking closely, you would be convinced that the crush of people, in principle, was being tugged in two directions. But as they crawled away from each other, these movements got hooked onto one another at protruding edges, braking and holding each other back. There were vehicles of all types; an automobile would try and get past a horse drawn vehicle but find itself nose to nose with another automobile coming in the opposite direction. Every time a space began to open, a cart packed with sheep would fill the space…[it was] like those pointless trails that you see ants make, going backwards and forwards along the same strip of earth, feverishly picking up grains of sand only to drop them a couple of centimetres further on…and perhaps, in fact, if a long-sighted, eternally optimistic god had leaned over Route Nationale 3 that day, he would have marvelled at all the busy activity he could see.”